Words Matter! Getting Current with Age-inclusive Language

By Nurse Writer Dow

January 19, 2023

I started following journalist and author Ashton Applewhite on LinkedIn as part of my research for an article about age-inclusive language. After diving into a collaborative she leads called Old School Clearinghouse, I knew I needed to challenge myself and learn what it means to write about older adults from a true strength perspective.

So I sought out Christina Peoples, a gerontologist who is part of the Old School network. Her social media platform engages the public in topics that empower people in later life. She promotes age-positivity through all her professional engagements. She inspired me to up my game as a health writer by unpacking this topic and looking at how to reframe aging!

Understanding the issue

Representing older adults equitably in our external communications requires commitment from authors and content managers. As with other aspects of our social identity such as race or gender, age carries implicit bias. Acknowledging this begins the shift toward positive changes in our language.

Ageism stereotypes people later in life, impacting how we think about them – and ourselves – as we age. Dr. Robert Butler coined the term ageism around 1970 after witnessing systemic injustices toward older adults. Misunderstanding and avoidance of aging issues transfer into negative feelings and thoughts about this life stage. What can result is prejudice and discrimination.

Self-assessment

After investigating and reflecting on authoritative material including the Reframing Aging Initiative, I realized my chief bias is that older people need help in general. This presumption is no doubt influenced by my training in Western medicine and years of providing chronic disease management as a nurse practitioner. Regardless, this view of aging people isn’t fair or accurate.

Other common misconceptions regarding elderhood are that

- chronic disease and complex social needs are the norm.

- physical decline and suffering are inevitable.

- dependency and disability eventually occur.

- most are unable to better themselves.

Perpetuating these ideas obscures the truth which is that every developmental stage has both benefits and challenges but ultimately contributes to the well-being of society. This is the type of aging experience I want to have:

- to find and maintain purpose,

- stay engaged with my community, and

- give back to other generations.

The last endeavor is known as generativity and honors the richness of experience and wisdom we have to share.

Shifting our troubled view of aging

We are all older people “in training,” yet this reality isn’t popular or discussed openly in Western culture. People unconsciously use words and phrases that set people who’ve grown older – say, those over 65 – apart. This creates an unspoken category of “other,” which is unattractive to most.

Because it is alienating, assigning labels to older adults such as “aged,” or “senior citizens” is no longer appropriate. It is important to unify rather than divide people over their age differences.

Depictions of people later in life as dependent or feeble produce an uneven power dynamic between older and younger persons and in health care between care providers and patients. This disempowers those seen as weaker, which drives decisions around crucial infrastructure such as funding, employment and the care we receive.

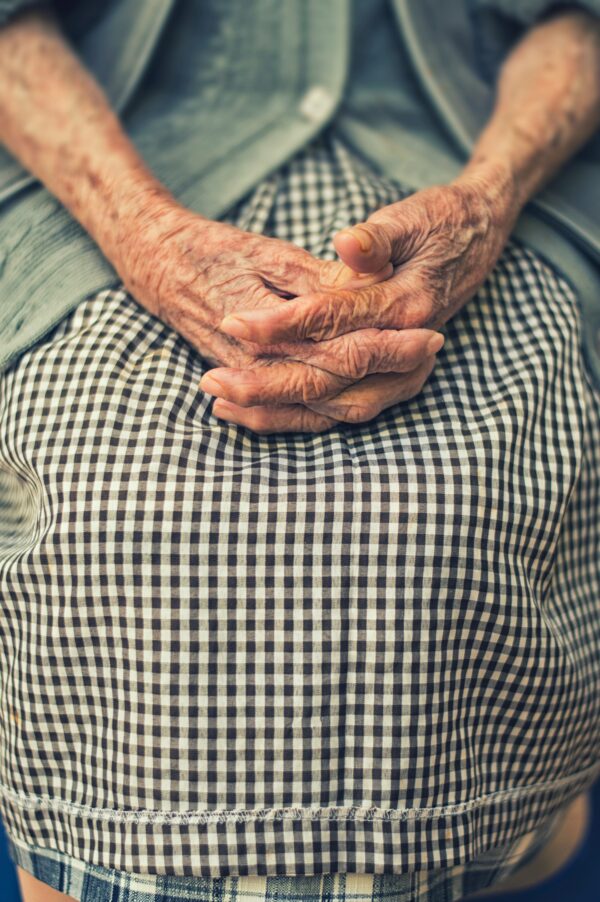

| What feelings do these images evoke? |

Choosing our words

A consortium of experts known as the Leadership Council of Aging Organizations joined together to advocate for health equity. Part of this effort was to improve the depiction of older adults in the medical literature.

Research shows that the current language used to describe older people does not sit well with the public. Also, media images too often focus on depressed faces, gnarled hands or an elder sitting alone. Out-of-date communication frameworks fail to accurately convey the progress being made in both geriatric medicine and aging services. These lopsided portrayals thereby obstruct needed updates in health policy.

As part of these improvement efforts, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) pioneered the campaign to remove bias by setting age-inclusive content guidelines for medical writers.

To test your knowledge, which of the following terms are acceptable?

- People in later life

- Senior citizen

- Older adult

- Older people

- Elderly

- Old

- Aged person

- Silver tsunami

- Geriatric*

- Senile

If you selected 1, 3 and 4 then you are ahead of the class! Using any of the remaining terms “connote(s) discrimination and certain negative stereotypes that may undercut research-based recommendations for better serving our needs as we age,” explains Manfred Gogol, MD in the Journal of The AGS.

*Geriatric(s) is still acceptable when describing that branch of medicine.

Tips for getting it right

When crafting an article or post, ask yourself if age is relevant to the story. If it is, consider simply listing the person’s age and avoiding any value statements. For example, instead of saying, “We are indebted to our favorite retiree, Mr. Evans, who remarkably worked until the advanced age of 87,” try: “Mr. Evans, 87, is our longest-serving volunteer and will be dearly missed.”

Additional tips from the Gerontological Society of America:

- Use unifying language like “we” and “us” rather than “they” and “them”

- “Older adult,” “older persons,” or “older people” are the preferred terms for describing people aged 65 and older

- Be specific about an age range (e.g., “American women 75 years of age and older”)

- Put the person first when speaking about an individual’s condition (e.g., say “a person with a disability” rather than “a disabled person”)

- Avoid terms that suggest the helplessness of people with diseases (e.g., instead of “suffering from arthritis” say “diagnosed with arthritis”)

- Avoid fatalistic phrases that suggest aging is an impending disaster (e.g., instead of “silver tsunami” say “the significant increase in the number of older adults”)

Keep in mind that if we live long enough, we all reach an advanced age. None of us wants to be labeled as incompetent or weak as we grow older. Language is a powerful tool at our disposal. As creators, we play a part in shifting public perception about aging by better choosing our words and avoiding stereotypes in our daily communications.